Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

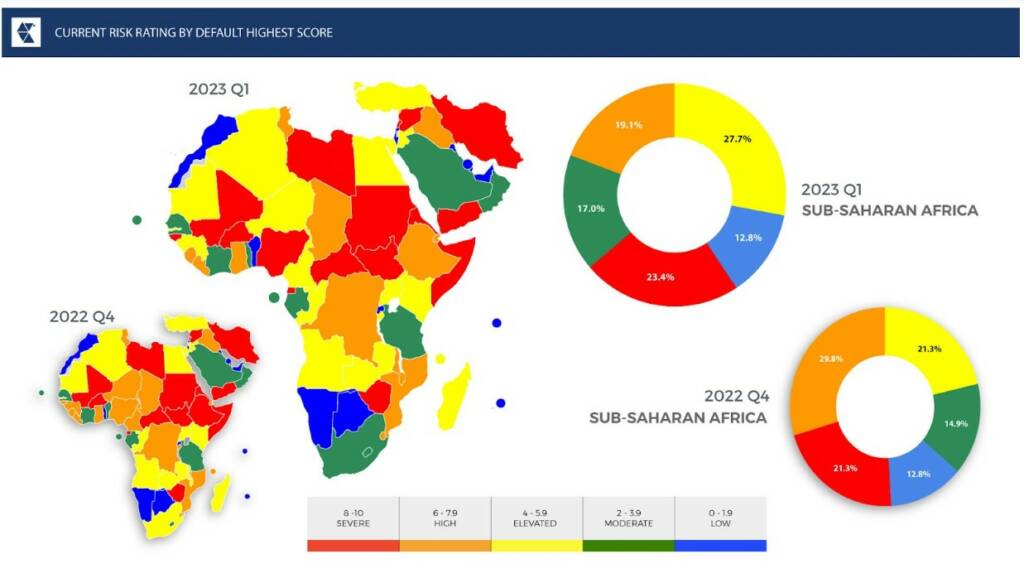

PANGEA-RISK CEO Robert Besseling anticipates some positive risk trends in Africa in 2023. Indeed, African economies will exceed global growth averages on the back of resilient commodity prices. Distressed debt will be treated to avoid chaotic default scenarios, while more foreign investment will return as diverse investors seek higher yield. Moreover, maturing democratic systems ensure that socio-economic grievances will increasingly be aired in the political arena, i.e., at elections, rather than on the street.

In 2023, most countries in Africa will see economic growth well above the global average rate, thus reverting to more optimistic pre-pandemic trends, at least relative to the rest of the world. Buoyant or resilient commodity prices, continued external support from multilaterals, and – in some cases – managed debt restructurings will underpin the economic recovery of countries still suffering the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

External risks persist, including the effects of the war in Ukraine, a resumption of travel restrictions due to the pandemic, continued disruption to trade and global supply chains, and the lagged peaking of inflation rates in emerging markets. But overall, African countries should see an improved economic outlook for 2023.

Despite slowing demand globally, commodity prices will remain high in 2023. After a dip in late 2022, oil prices are expected to average above $80 per barrel this year, which is good news for nascent producers in Africa. Perhaps worryingly, some of Africa’s largest oil producers will fail to benefit from higher prices as output continues to drop in Angola, Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea.

Yet, Nigeria’s efforts to curb crude oil theft may be reversing a long-time downward export trend. Meanwhile, new fossil fuel projects in East and West Africa are more likely to be signed off as long-term gas and oil prices remain high. Mozambique, Senegal, Mauritania, and Guinea will start natural gas exports in 2023, while Tanzania may see a long-anticipated final investment decision on gas projects. Investment commitments on major oil and gas infrastructure, including pipelines and East and West Africa, should also be expected this year.

Metal prices will remain volatile, but a floor under base metal prices will be kept in 2023. Gold started the new year with prices at a six-month incline and analysts believe the rally has further to go in 2023. This is good news for major producers Tanzania, Ghana, and South Africa, although divestments are ongoing in Mali and Burkina Faso due to insecurity and reputational risks. Major producers of fourth industrial revolution metals such as DRC will see concrete benefit to their economies as demand for components remains scarce globally.

Debt restructuring to avoid default

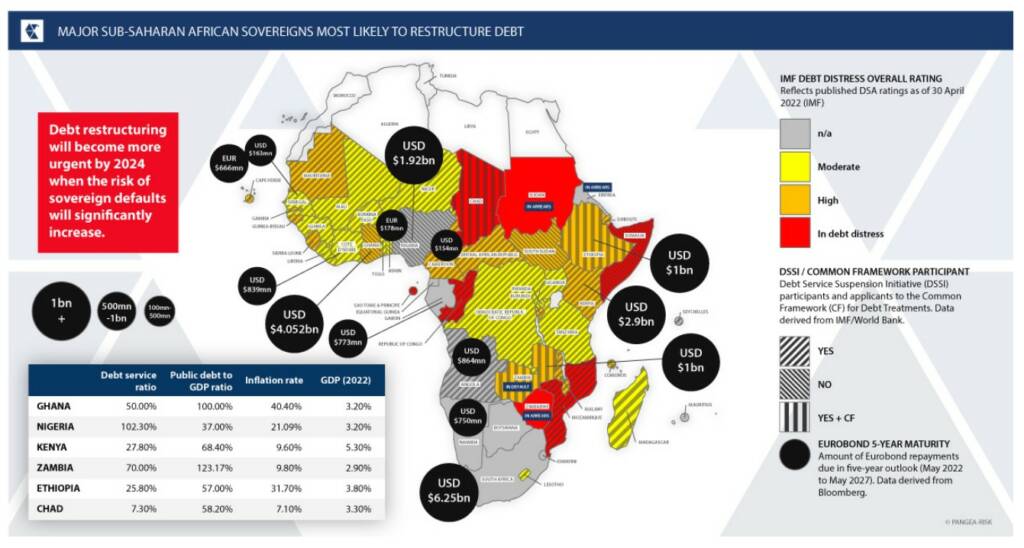

At its autumn 2022 meetings, the IMF did not add any countries to its list of debt-distressed countries, or those at risk of falling into debt distress. That will probably change at the April 2023 meetings jointly held by the Fund and World Bank – expect more African countries to make the debt distress shortlist. Sub-Saharan African long-term loans have more than doubled to $636 billion in the decade to 2021 — that exceeds the combined gross domestic product (GDP) of more than 40 African nations.

Given the elevated debt levels, African governments are allocating a larger share of their revenues to servicing external debt. The compounding effects of high debt service costs along with a domestic currency depreciation have increased exchange rate risks for countries with high external debt. Eurobonds and Chinese loans are at highest risk of default – African nations owe China about $84 billion, by conservative estimates.

The World Bank says that support for international debt restructuring might be required. Last year, Pangea-Risk accurately assessed that at least six African countries would restructure their debt, namely Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia. All six countries have since commenced some form of domestic or external debt treatment, while Chad has completed its external loan reprofiling – at least for now.

This may be a positive development, as multilaterally coordinated and well-managed debt treatments are more likely to avoid chaotic defaults such as those in Mozambique in 2016 and Zambia in 2021. A calibrated debt reprofiling in Angola and Republic of Congo have turned around these countries’ economies and rendered their debt to more sustainable and affordable levels. Eurobond holders and commercial creditors may fear significant haircuts on African obligations, but without restructuring, more debt is more likely to default and trigger a wider financial crisis.

Elections to mitigate unrest risks

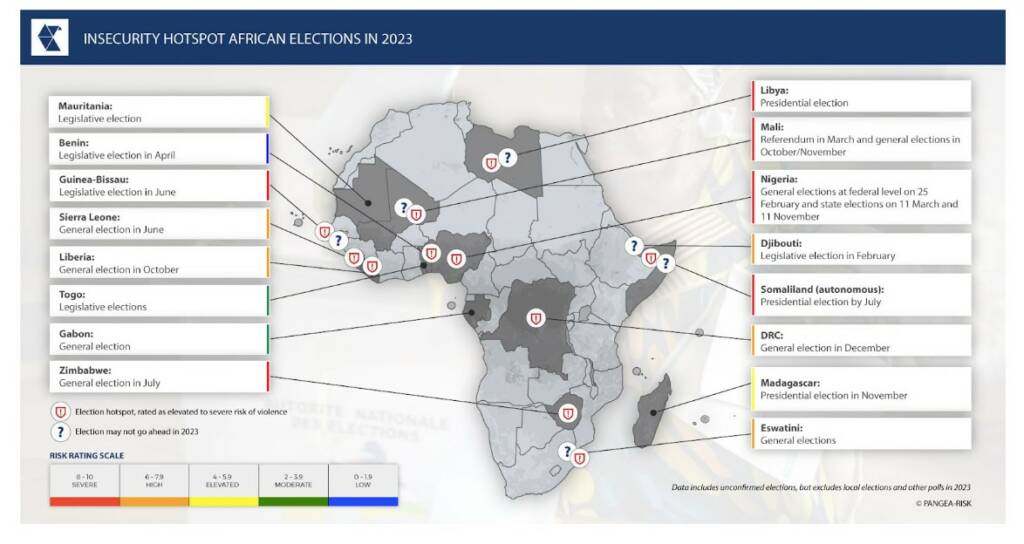

Some 16 African countries are scheduled to hold elections over the coming year. In 2023, several hotly anticipated votes are taking place in the backdrop to rising costs of living, tight fiscal regimes, and broader insecurity. Some of these elections may trigger political instability and, potentially, unrest. In fact, we have identified more than ten countries where upcoming elections may drive insecurity that should be monitored over the course of this year. Meanwhile, preparations for about 13 more elections in Africa in 2024 alone will also drive similar risks of political instability, civil unrest, and policy uncertainty this year.

However, elections should not always be interpreted as a “risk”, which is a common perception by country risk analysts. Indeed, notable polls in 2022, including in Angola and Kenya, portray an increasingly steady political climate and a democratically mature trend developing on the African continent, which will set the tone for upcoming votes in 2023.

Elections increasingly offer a chance for electorates aggravated by inflation, debt, and other grievances to vote out incumbents and seek political renewal, thus avoiding broader instability. Country risk analysts too often warn of elections as indicators of insecurity and political instability, which is generally a fair assessment. But let’s not forget the opportunity that elections hold for both local electorates and foreign investors. Elections can and do often mitigate political risk, rather than drive it.

Australia

Australia Hong Kong

Hong Kong Japan

Japan Singapore

Singapore United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates United States

United States France

France Germany

Germany Ireland

Ireland Netherlands

Netherlands United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Comments are closed.